Although the exact history of spectacles can be disputed, the fact that 17th Century England kept records gives us some factual anecdotes about the craft of spectacle making. The city of London had Guilds, which improved trade organizations, protection of trade and increased solidarity within the craftspeople. Each member contributed to the guild, and could benefit from the funds in illness and older age.

John Cuff, Master of the Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers. By Johann Zoffany, 1772. © The Royal Collection.

In 1629, The Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers (WCSM) was incorporated by the Royal Charter. The Worshipful Company carried out inspection visits to businesses in the City of London and seized products that they deemed sub-par, these were seized and smashed on Cannon Street’s London Stone! Mostly concerned with lens quality, leather frames caused particular ire to the Company’s inspectors. Records show that in 1692, leather frames were confiscated from esteemed optician John Yarwell, although in 1669 poor quality whited copper frames were “left alone” and their lenses smashed. It is speculated that this could be a reason for the growth in using horn instead during this period.

Melchior Schelke, a very rare example dated 1663, made out of buffalo horn with filigrees of hearts and clovers, BOA Museum.

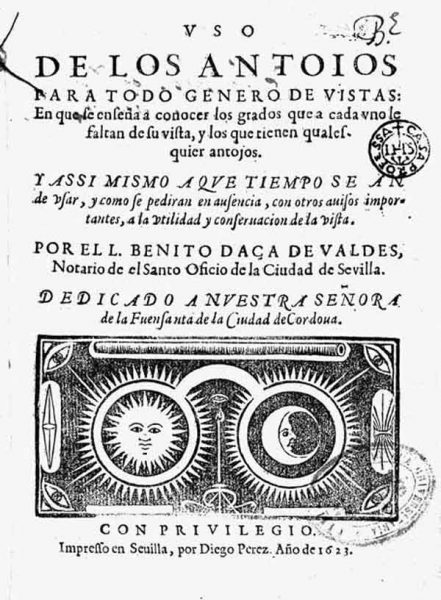

In 1623 the Spanish writer B. Daza de Valdes, known for his work on lenses, spectacles and telescopes, published ‘Vso de los antojos para todo genero de vistas: en que se ensena a conocer los grados que a cada vno le faltan de su vista, y los que tienen qualesquier antojos. Y assi mismo a que tiempo se an de vsar, y como se pediran en ausencia, con otros auisos importantes, a la vtilidad y conseruacion de la vista’. In it, he describes instances where a manufacturer of spectacles advises a customer, whose bow spectacles kept dropping off, that his leather frames would stay on his nose much better than a silver pair, due to leather’s flexible and light nature. The customer rejects this and the suggestion of adding loops to the side of the spectacles to hang on to the ears, for its association with older people. A classic example of fashion over functionality!

Although there are no remaining examples of the deviant leather spectacles, we can turn to 17th century paintings for an idea of what they might have looked like in form. This painting from 1641 depicts a pair of spectacles from this era. The design—the bow spectacle—has no temples and was meant to hang by the bridge of your nose. The would have to be hand held, leaving no hand free for a mug of coffee if you were reading. Although fashion in paintings are not completely accurate, the style of spectacles in Jan Steen’s painting, dated 1658-65, seem to be similar to the bow. Both portrait titles, the Botanist and the Rhetoricans, also hints at the types of clientele that required reading glasses. Only the learned and literate classes would have a need for glasses, with the increase in literacy and more affordable ways of producing spectacles, this is no longer the case. Over time, the techniques for spectacle-making have changed and leather has once again found its way into spectacle designs.